The novelty of 3D printing is that you can, in a way, teleport an object from one location to another, at great distance, in just a matter of minutes. Of course, the materials you make with a 3D printer will really only be replicas of the real thing, made out of a synthetic fiber, similar to the way that a standard printer can replicate a photo using ink ribbon.

The novelty of 3D printing is that you can, in a way, teleport an object from one location to another, at great distance, in just a matter of minutes. Of course, the materials you make with a 3D printer will really only be replicas of the real thing, made out of a synthetic fiber, similar to the way that a standard printer can replicate a photo using ink ribbon.

But that novelty can be useful. For example, when members of the International Space Station needed a wrench to repair a piece of equipment, they were thankful to have already received a 3D printer in a previous supply shipment. This made it easier to get a working replica of the wrench; otherwise, they would have had to wait months or longer to get a simple wrench. Depending on the repair, of course, this could be a catastrophic amount of time to have to wait.

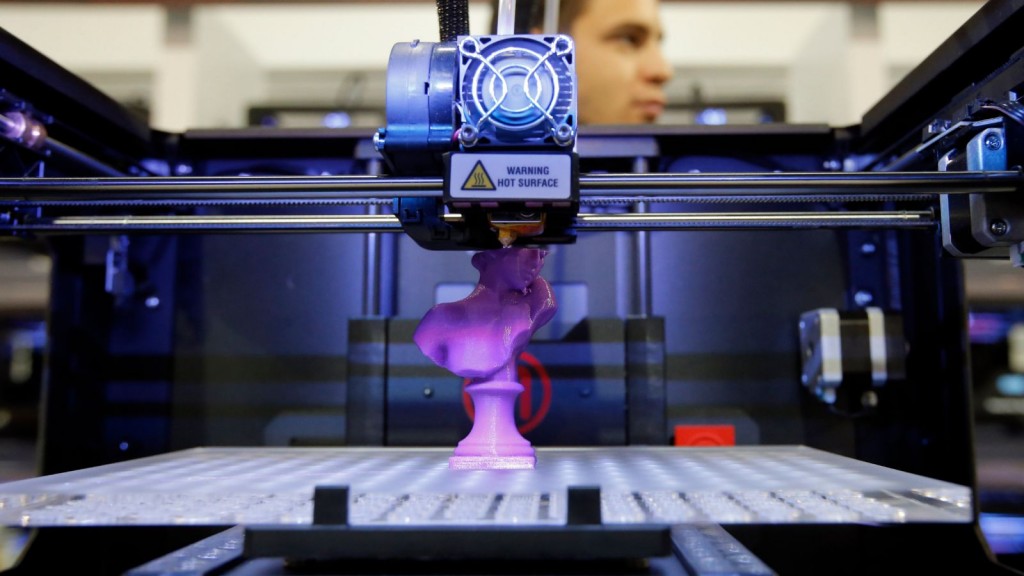

What about the rest of us, though? Do we need 3D printers in our daily lives? Some might argue that they are not yet practical, but research shows that 3D printing can address the needs of the average person. For example, a team from Wake Forest University has figured out a way to combine living cells with a special gel which can be installed in a 3D printer to print living human body parts.

Now, Dr. Anthony Atala of the Wake Forest University Institute for Regenerative Medicine says, “We are actually printing the scaffolds and the cells together.”

The study leader goes on to say, “We show that we can grow muscle. We make ears the size of baby ears. We make jawbones the size of human jawbones. We are printing all kinds of things.”

In the study, published in the journal Nature Biotechnology, the authors explain the process: “The correct shape of a tissue construct is obtained from a human body by processing computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data in computer-aided design software.”

Of course, we are still years—probably decades—away from this becoming a regular medical practice, but the implications for the future are quite impressive, and encouraging.